OECD Ecosystem Strengthening Learning Journey Series Session Two

Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning of Innovation Ecosystems

Authored by Benjamin Kumpf, Nicole Paul, Shad Hoshyar and Matilde Ferretti

This note summarises the discussion of the virtual seminar on September 24th, 2025, on innovation ecosystem strengthening, convened for development funders by the OECD Innovation for Development Facility in collaboration with the International Development Innovation Alliance (IDIA). This seminar is part of a nine-month learning journey that aims at advancing peer-learning among funders and generating new insights to inform better practices.

Why Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Matters in Innovation Ecosystems

Sir Geoff Mulgan opened the session by highlighting a core challenge: innovation ecosystems are complex, dynamic, and often messy. Whether you're a policymaker, funder, or investor, understanding these systems requires clarity of purpose. Are you mapping actors, diagnosing maturity, or identifying gaps? Without a clear objective, analysis risks being ineffective or misleading. To navigate this complexity, Geoff offered two heuristics:

1) “All models are wrong, but some are useful”

Frameworks like the Global Innovation Index (GII) and OECD Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Diagnostics provide valuable data—especially for low- and middle-income countries. Tools such as the GII Data Explorer now include regional briefs for Africa, offering snapshots of innovation performance, trends, and key players in academia and the private sector. (Thanks to Lorena Rivera Leon from WIPO for sharing these resources.)

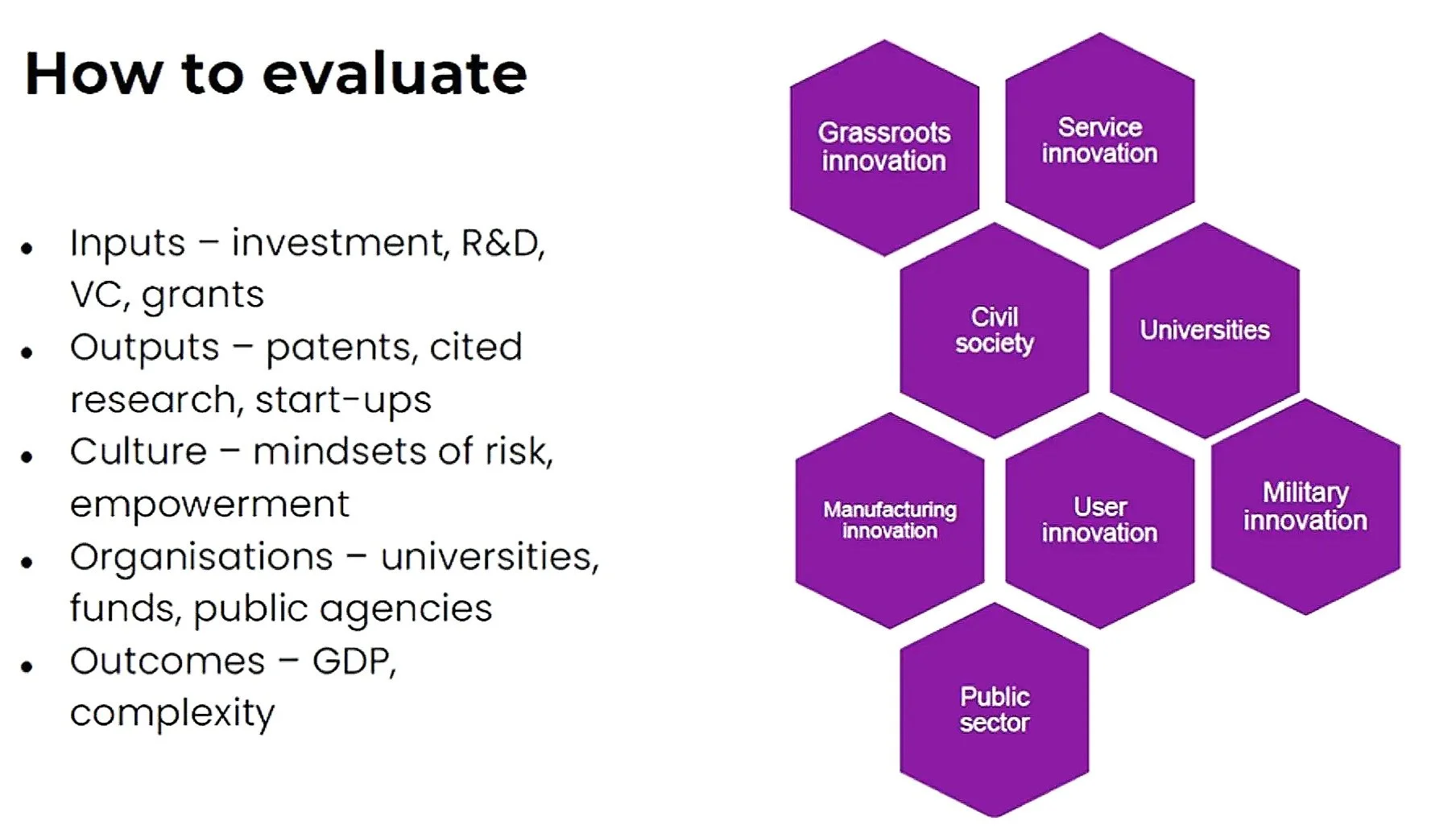

However, using these metrics effectively requires more than just access to data. Development funders should consider:

Sense-making capacity: Are there people who can interpret indicators like patent counts or research citations in context?

Novelty vs. adoption: Is generating new ideas more important than adapting existing ones? Often, the latter drives long-term success.

Capturing diverse innovation: Many frameworks overlook informal, social, and grassroots innovation, especially in LMICs.

Purpose of measurement: Is data collected for reporting, or to generate actionable insights for ecosystem actors?

Figure 1: Mulgan, Geoff. 2025. How to evaluate innovation ecosystems.

2) “The map is not the territory”

Innovation ecosystems are shaped not just by infrastructure and capital, but by people, trust, and relationships. Mapping exercises can reveal missing links, bottlenecks, and opportunities but only if done with a clear purpose and audience in mind.

Some maps help entrepreneurs identify funding and connections; others expose geographic inequalities between urban and rural regions. The most useful insights often emerge at the level of clusters, sectors, or regions—such as digital startups, creative industries, or agricultural innovation. Understanding these granular dynamics is essential for designing interventions that reflect the real distribution of innovation activity, rather than treating ecosystems as uniform.

From Metrics to Meaningful Insights

Moderated by Angela Hanson (OECD OPSI), the fishbowl featured a dynamic exchange among experts including: Rhett Morris (Common Good Labs), Carla Alvial Palavicino (Climate KIC), Joe Watkins (IOD PARC), Peer Priewich (GIZ), and Sir Geoff Mulgan (UCL), focusing on social network dynamics, inclusion, and cost-effective MEL strategies.

Participants contrasted the usefulness of mapping relationships with the limitations of traditional metrics. For example, Carla and Joe shared experiences mapping circular economy clusters in cities like Bengaluru and Nairobi, noting how visualising the connections between businesses, governments, and universities was often more helpful than relying on standard indicators. Maps can expose missing actors and open opportunities for action, while static measures (like patent counts) often only satisfy funders’ accountability requirements.

Ecosystems are communities of people: as Rhett Morris from Common Good Labs emphasised, ecosystems are better understood as communities of human beings rather than abstract networks. Entrepreneurs, researchers, mentors, investors, and policymakers are all connected through relationships that shape learning and innovation. Rhett shared main insights from research in Kenya and India, including: invest in understanding who leads incubators and accelerators, as the findings of this study suggest that individuals who have direct entrepreneur experience are much more effective in leading such nodes of an ecosystem, compared to people who never dared to launch a business. Several participants echoed the importance of social capital and connections, emphasising that understanding “who is useful to whom” (who provides information, funding, contracts, or mentorship), can reveal both the strengths and the missing links in an ecosystem. Sir Geoff Mulgan reinforced this point by noting that migration patterns are often overlooked but are in fact fundamental tests of whether ecosystems can retain talent.

“Need for granular insights”

Another recurring theme during the conversation was the need to move beyond national-level averages. Participants pointed out that in practice, collaboration dynamics vary widely between subsectors: what works in circular economy partnerships may not apply to data centres or life sciences. Geoff added that while aggregate indices like the GII have value, the real insights come from zooming into clusters or sectors where the dynamics of trust, investment, and policy are highly differentiated. Participants agreed that focusing on this granular level enables more targeted and meaningful interventions.

Focusing specifically on agricultural innovation, co-innovation between researchers, farmers, and grassroots innovators is essential, yet often overlooked. FAO colleagues emphasised the importance of monitoring not just the presence of diverse stakeholders but also the quality of their interactions. They shared how social network analysis tools (including simple methods like “pen-and-paper” net-mapping and online platforms such as Graph Commons) can help surface who is connected, who is excluded, and whether women, smallholder farmers, or informal entrepreneurs are genuinely part of the system.

Cost-effective MEL Strategies

A strong message from the discussion was that effective monitoring and learning does not always require large budgets. Several participants highlighted cost-effective MEL strategies, such as adding simple network-mapping questions to midterm evaluation interviews. Participants shared how even modest data collection exercises can yield actionable maps of entrepreneurial communities. For example, anonymised mobile phone data (already used to track economic activity during the pandemic) could offer a low-cost, underexplored resource for understanding real flows of talent and knowledge.

Part Two: Technical Workshop

1) Tracking Change in Innovation Ecosystems: From Policy to Startups

Led by Eleanor Tuck (Programme Director, Chemonics UK) and Anne Thibault (Chief Impact Officer, Fund for Innovation in Development - FID), this workshop brought together funders and practitioners to explore how to define and monitor indicators for innovation ecosystem strengthening. The session focused on the challenges of capturing policy change, startup maturity, and broader systemic transformation in complex, multi-actor environments.

Eleanor Tuck shared lessons from the RISA programme, which supports innovation ecosystems across six African countries. Initially relying on traditional MEL tools, the team found these inadequate for capturing complex system dynamics. They adapted IDIA’s framework to track progress across four impact levels—from planning to sustained results—while preserving nuance. Analysis revealed three strategic pathways driving success: Partnerships & Networks, Research to Commercialisation, and Policy Environment, supported by crosscutting themes of Gender Equity & Social Inclusion (GESI) and Informed Human Capital.

Figure 2: Tuck, Eleanor- RISA programme, 2025. Critical pathways to understand ecosystem change.

To support data visualisation and communication, the team used Aktek, an information management system that feeds into interactive dashboards. These dashboards allowed real-time tracking of project progress, mapped stories of change, and linked quantitative indicators to specific ecosystem goals. Eleanor illustrated the value of this MEL approach with examples from Impact Investing Ghana and the RISA-KECC agri-tech initiative in Nigeria, showing how the framework enabled nuanced assessments of project progress.

In the second half the session, Anne presented FID’s approach to measuring innovation ecosystem change. FID uses a tiered funding model based on innovation maturity and a performance matrix that spans four levels: application, project, portfolio, and ecosystem.

Figure 3: Thibault, Anne - Fund for Innovation in Development. Tiered funding model.

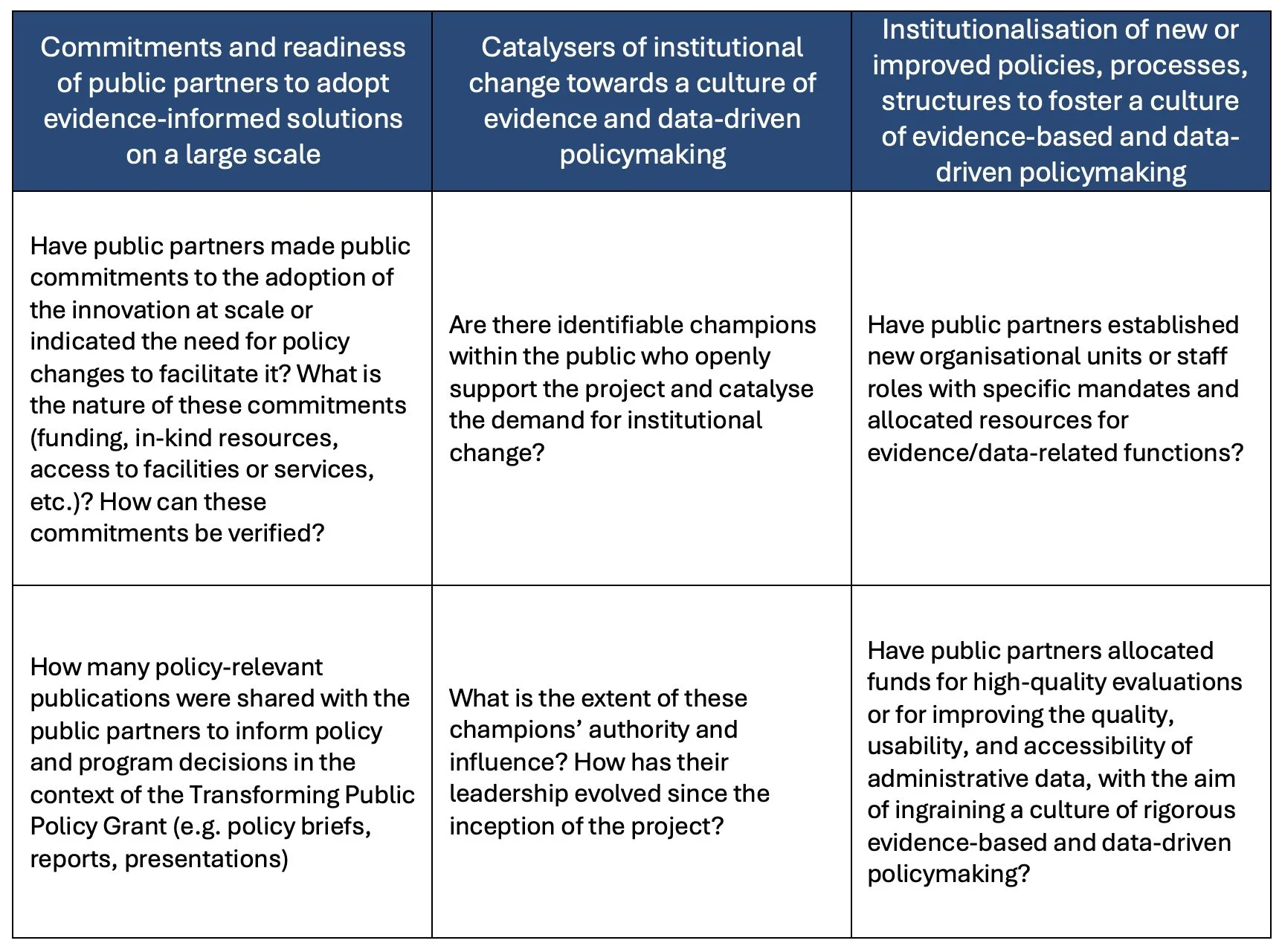

In developing its MEL framework, FID found that quantitative indicators were insufficient for capturing ecosystem transformation and measuring institutional and systemic shifts. To address this, the team developed a complementary qualitative tool in the form of a structured questionnaire, designed to assess the degree of institutionalisation as well as the readiness of public partners in scaling innovation.

Table 1: Thibault, Anne - Fund for Innovation in Development. Qualitative questionnaire to determine readiness of public partners.

The tool generated rich insights into how evidence flows into policymaking processes, who leads data-driven decision-making, and how committed public actors are to sustaining innovation. However, Anne also noted limitations, including self-reporting bias and inconsistent data quality across projects. Importantly, the data revealed the pivotal role of government champions in driving or stalling evidence-based policymaking.

The discussion also emphasised the role of champions in catalysing innovation within government. Anne highlighted the trade-offs between political influence and sustainability: while high-level champions can accelerate progress, their departure can stall momentum. More durable change often comes from mid-level officials and institutional teams that embed innovation into public structures.

2) Innovation Beyond the Formal Sector: Non-traditional Indicators

The workshop was led by Glenda Kruss (Executive Head, Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators) and Nazeem Mustapha (Research Director, Human Sciences Research Council) from South Africa’s Centre for Science, Technology, and Innovation Indicators (CeSTII), which was created to build national capacity for R&D surveys and STI indicators.

While early efforts focused on global comparability, the emphasis has shifted to locally relevant data that supports long-term planning and inclusive development.

Following the 2018 revision of the OECD Oslo Manual, CeSTII adopted new strategies: re-analysing existing data, designing new indicators, exploring underrepresented sectors like agriculture and the informal economy, and developing frameworks for inclusive innovation. This led to advances like green R&D tracking and more nuanced firm-level analysis.

Presentations by Dr. Glenda Kruss and Dr. Nazeem Mustapha sparked discussion on how to better capture innovation in informal economies. With 20% of South Africa’s workforce in the informal sector, innovation is often local and capability-driven—yet overlooked by traditional surveys. CeSTII’s work highlights the need to recognise diverse innovators and develop tools that reflect the full spectrum of innovation activity.

Figure 4: Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators, South Africa. 2025. Maturity index: degrees of in/formality to inform policy strategies.

3) Outcome Harvesting: Capturing Change in Complex Innovation Ecosystem

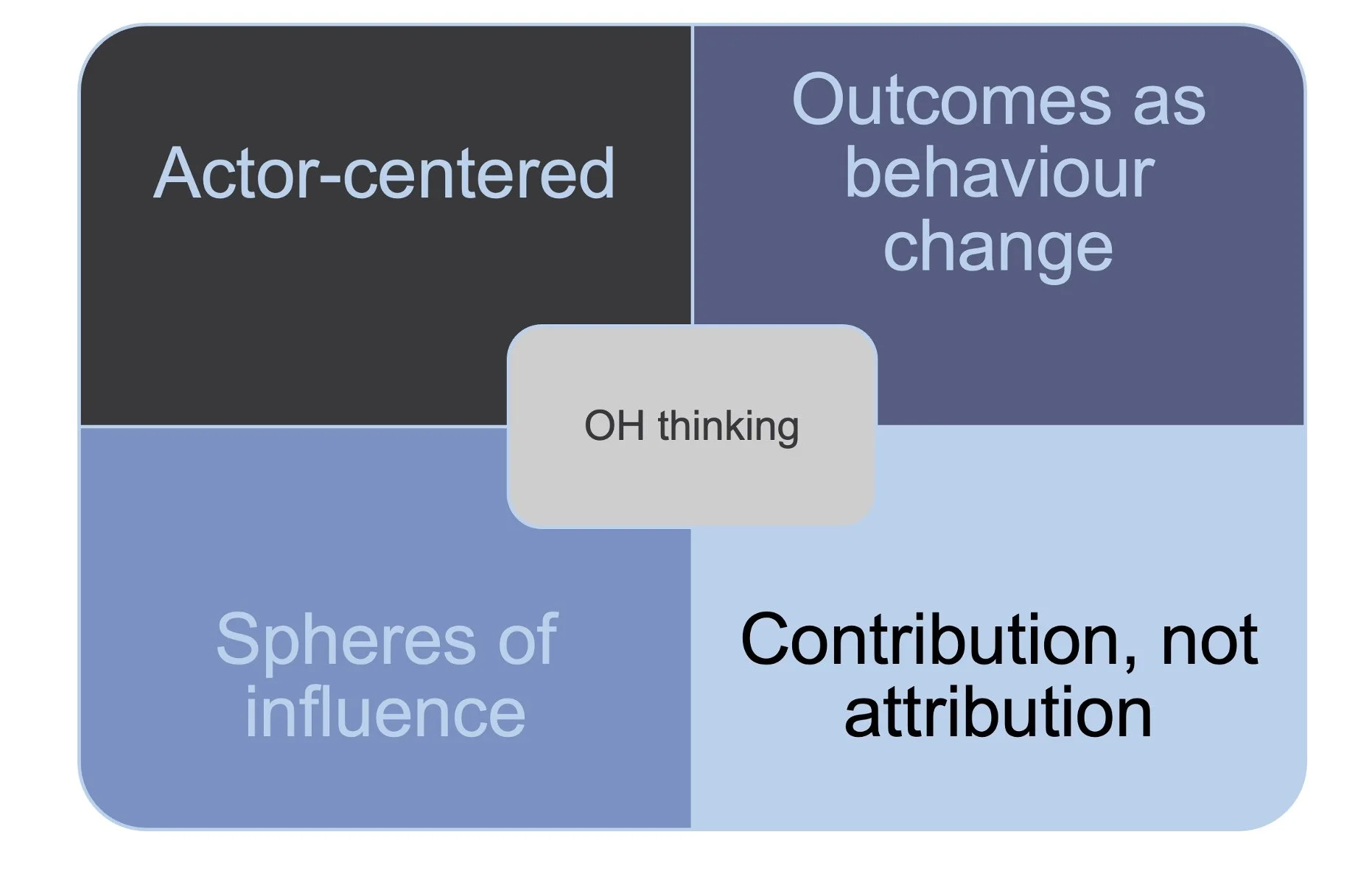

In a workshop led by Julius Nyangaga (Right Track Africa) and Richard Smith (RDS Consulting), participants explored Outcome Harvesting (OH) as a flexible, people-centered method for evaluating innovation ecosystems. Unlike traditional MEL approaches, OH focuses on behavioural change and contribution, asking what changed, who changed, how the project contributed, and why it matters.

Julius shared examples from FCDO-funded programmes, including a Nigerian initiative that improved IP filing processes through targeted training and accelerator support. The result: patent filings jumped from 22 to 73 in one year. He emphasized that OH helps uncover linkages between actors and surfaces outcomes that are often missed by standard reporting.

Richard positioned OH as ideal for complex systems where change is non-linear and influenced by many actors. He introduced four key concepts: identifying who changed, defining outcomes as observable behaviours, distinguishing between spheres of control, influence, and interest, and recognizing that most outcomes result from multiple drivers. OH makes visible the hidden dynamics of how ecosystems evolve.

The discussion highlighted that OH is most effective when applied to specific interventions, not entire ecosystems. As Peer Priewich noted, “ecosystems are the context, but OH helps us understand the role of particular programs within that context.” Participants agreed that relationships and behaviours are as critical as outputs, and that articulating the significance of change is essential for learning and adaptation.

Ultimately, OH enriches theories of change, validates assumptions, and reveals new pathways of influence. Its participatory nature ensures insights are context-sensitive, actionable, and grounded in real-world complexity—making it a valuable tool for funders and practitioners working to strengthen innovation ecosystems.

Source: Richard Smith - RDS Consulting, 2025

Moving Forward

The next seminar will take place on 30 October 2025, focusing on Inclusivity in Innovation Ecosystems. Participants will explore how to frame inclusive innovation and identify effective ways to advance inclusive decision-making processes and equitable outcomes. Colleagues are encouraged to bring examples, tools, challenges or questions from their work, which will help shape a shared approach that is grounded in practical realities and responsive to emerging challenges.

If you are practitioners working on strengthening innovation ecosystems in LMICs and want to get involved, please get in touch via indef@oecd.org