OECD Ecosystem Strengthening Learning Journey Series Session One

Measuring the Maturity Levels of Innovation Ecosystems

Authored by Benjamin Kumpf and Shad Hoshyar

This note summarises the discussion of the virtual seminar on July 23rd 2025 on innovation ecosystem strengthening, convened for development funders by the OECD Innovation for Development Facility in collaboration with the International Development Innovation Alliance (IDIA).

Why ‘Innovation Ecosystems’?

Over the past decade, the discourse on research and innovation ecosystems has gained steady traction across academic, policy and international development cooperation domains. This increased interest among governments and funders reflects a growing recognition that complexity is a defining characteristic of development challenges, and that linear models often fall short in capturing the intricate interdependencies at play within our social, economic and environmental systems. Ecosystem thinking offers a more nuanced lens, capable of capturing the dynamic relationships that drive innovation to promote inclusive growth and social resilience.

At the same time, an increasingly robust evidence base on innovation scaling – particularly with regard to local enabling environments – has reinforced the relevance of ecosystem frameworks in shaping policy and practice.

Building on these movements, a small but growing number of bilateral funders and members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) are implementing programmes specifically aimed at strengthening research and innovation ecosystems in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). Many more are reinforcing these efforts by investing in distinct ecosystem elements, including incubators, accelerators, research institutions and individual social entrepreneurs.

Advancing learning and practice among development funders

In 2024, several DAC members asked the OECD Innovation for Development Facility to help strengthen peer-learning and knowledge transfer among funders on innovation ecosystems. In response, the OECD is convening a ten-month peer-learning journey for DAC members, multilateral development banks and other funders to share lessons learned, and identify new opportunities for collaboration. Funded by the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), this joint initiative with the International Development Alliance (IDIA) consists of monthly virtual seminars and an in-person meeting in spring 2026. Building on insights from OECD and IDIA’s previous work on innovation scaling and ecosystem strengthening, this learning journey will take stock of ongoing efforts, promote mutual learning, and elevate the voices of partner governments, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa.

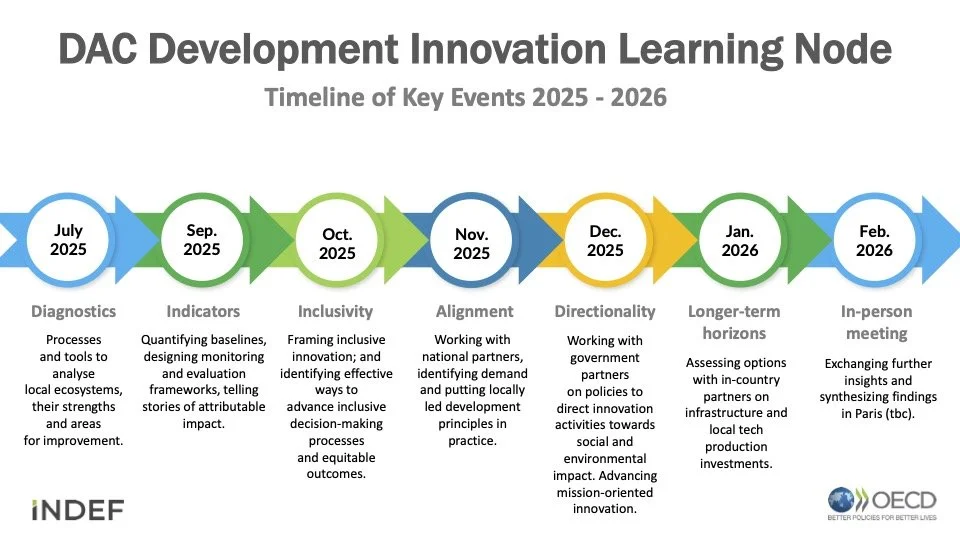

Over the course of this learning journey, the OECD will produce a mapping of ongoing efforts, a synthesis paper on monitoring and evaluation best practices, and summary notes of each seminar. This learning journey builds on OECD’s 2025 consultation with DAC members, which brought together development innovation experts to identify the most relevant peer-learning themes, as reflected below:

Figure 1: Timeline of OECD IDIA Innovation Ecosystem Strengthening Learning Journey 2025-26

How to assess the maturity levels of local ecosystems: insights from the peer learning seminar in July 2025

On 23rd July 2025, the OECD Development Innovation Facility and IDIA convened over 50 innovation experts from across the DAC membership, multilateral development banks – including the Asian Development Bank, the African Development Bank, the West African Development Bank – and other funding agencies, such as the Global Innovation Fund and the French Fund for Innovation in Development. The first session in the learning journey focused on assessing the maturity of innovation ecosystems in LMICs, and aimed to:

Provide participants with an overview of the entire learning journey, its rationale and planned outputs.

Share practical approaches for framing and assessing innovation ecosystems to inspire critical reflections and promote better practice.

Validate a list of existing, globally available data sources to assess innovation ecosystems and crowd in additional methods to obtain relevant data.

Moderated by Benjamin Kumpf, Lead of the OECD Innovation for Development Facility, the seminar featured a dynamic line-up of experts, including Dr. Emmy Chirchir, Senior Programme Officer at International Development Research Centre (IDRC); Dr Emmeline Skinner, Adviser at the UK FCDO East Africa Research and Innovation Hub; Hannah El Mufti, MEL Director at Chemonics; Umar Kabo Idris, Senior Programme Officer at Results for Development; Nee-Joo Teh, Head of Global Alliance at Innovate UK; Dr Caroline Paunov, Senior Economist at OECD, Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) Directorate; Luke Mackle, Policy Analyst at OECD, STI Directorate.

Framing innovation ecosystems

Benjamin Kumpf opened the session by highlighting that innovation ecosystems are defined and approached differently across the DAC membership and beyond. Currently, the primary ecosystem concepts used among DAC members include: business, entrepreneurial, knowledge, research and innovation ecosystems. Some actors focus solely on start-ups, others on governments and regulatory challenges, while a few adopt a triple helix lens, incorporating public, private and academic sector perspectives. This mismatch results in uncoordinated approaches and collaboration models among the DAC members and, at times, within institutions. Additionally, this fragmentation exacerbates the existing challenges that donor organisations face when strengthening research and innovation ecosystems.

In light of this challenge, the OECD is assessing with members of the innovation network whether a definition that the DAC endorses might help establish a common language, which in turn could strengthen collaboration at the country level. This question will serve as a thread throughout the learning journey, and aims to support DAC members and other funders to identify collective opportunities for improved coordination and efficiency in their innovation work.

During this session, the OECD invited participants to explore different definitions and frameworks, and reflect on which ones are suitable for their organisational contexts and objectives. IDIA, for example, defines an innovation ecosystem as a system made up of enabling policies and regulations, accessibility of finance, informed human capital, supportive research, markets, energy, transport and communications infrastructure, a culture supportive of innovation and entrepreneurship, and networking assets, which together support productive relationships between different actors and components of the ecosystem.

The working definition of an innovation ecosystem used to ground the first seminar was “innovation ecosystems are place-based, multi-purpose systems, at the national or sub-national level, with economic and societal objectives”.

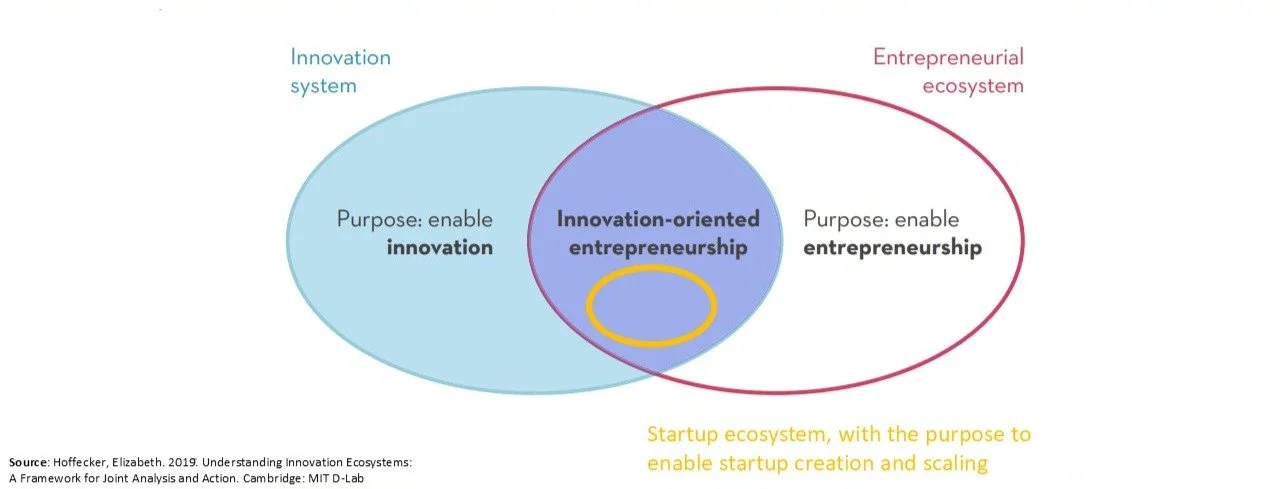

A key reference point shared during the session was Elizabeth Hoffecker’s 2019 model, which illustrates how the concept of an innovation ecosystem overlaps with adjacent ones, such as entrepreneurial or innovation ecosystems (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Hoffecker, Elizabeth. 2019. Understanding Innovation Ecosystems: A Framework for Joint Analysis and Action. Cambridge. MIT D-Lab. Elaboration of the start-up ecosystem by OECD.

Participants agreed that framing a social-technological system as an innovation ecosystem or an adjacent system, such as a research or entrepreneurial ecosystem, requires defined system boundaries; and that such boundaries need to be agreed at the country level to establish a common understanding among the national government and other innovation ecosystem partners and funders. Considering this, participants agreed that shared ambition among innovation ecosystem stakeholders can be considered a prerequisite for developing a baseline to assess the maturity level of a local system.

Assessing innovation ecosystem maturity levels with national partners

Dr Emmy Chirchir introduced the Network of Innovation Agencies in Africa, a collaborative initiative that brings together national and regional stakeholders to promote and advance innovation in Africa. The network aims to support innovation agencies in Africa to co-design collaborative projects, peer-to-peer learning, and targeted capacity building to address regional challenges. Noting the initiative’s transboundary influence and reach, the OECD invited the Network to collaborate with OECD and IDIA in shaping the peer learning journey during future sessions.

Building on Dr Chirchir’s remarks, partners from the UK FCDO-funded Africa Technology and Innovation Partnerships (ATIP) programme contributed their experiences and lessons learned from across the initiative’s first five years.

Together, all speakers underscored several common challenges related to innovation ecosystem diagnostics: the lack of widely used frameworks that help assess ecosystem maturity levels in LMICs, the lack of data related to ecosystem maturity, and the challenge of identifying and navigating existing data sets.

In the absence of approved in-house diagnostic tools, ATIP drew from IDIA’s frameworks to help frame the concept of innovation ecosystems and define boundaries of what is and is not in scope, together with national partners from local innovation agencies and relevant ministries in partner countries. Past experiences suggest that the advantages of this framework are:

It promotes a common language among stakeholders, which helps conduct stakeholder mapping.

Its emphasis on scaling highlights the importance of analysing the maturity level of an innovation ecosystem, not only to generate early-stage solutions, but to provide an enabling environment for solutions to scale and drive sustainable impact.

Figure 3: IDIA Actors in an Innovation Ecosystem.

In the context of the ATIP programme, the speakers also elaborated on two approaches they used to fill current gaps:

Working with an approved diagnosis framework, namely the Applied Political Economy Analysis (PEA). This was used by ATIP implementing partners to understand policy landscapes, financing gaps and stakeholder dynamics.

Working with government partners, mainly national innovation agencies, to validate existing assessments. This involved jointly developing or reviewing existing stakeholder maps, reviewing key policy documents, and bringing in experts from key sectors such as agriculture or health, depending on the specific objectives of the programmes. FCDO colleagues and partners from implementing agencies stressed that national government ownership and collaboration were central to understanding innovation ecosystem maturity levels and, in turn, were pivotal to long-term programme success.

Engaging citizens in innovation ecosystem strengthening and leveraging frontier technologies

Policy experts from the OECD STI Directorate (Working Party on Innovation and Technology Policy) presented insights from their ongoing work to strengthen innovation ecosystems for frontier technology development. While their policy examples were drawn from high-income country contexts, their approaches – with particular regard to supporting and de-risking collaborative innovation and research between ecosystem stakeholders – are adaptable to ecosystems with different maturity levels, including in LMICs.

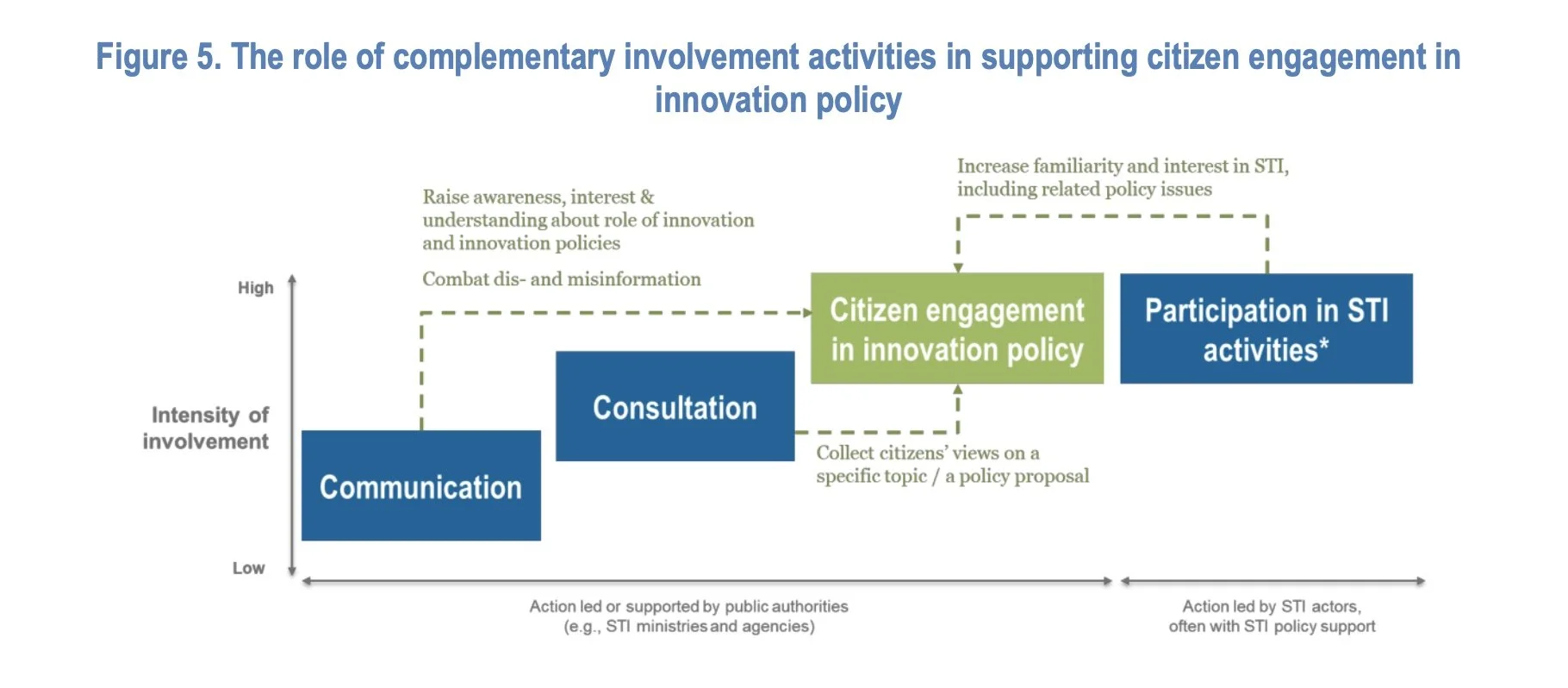

Complementing lessons from the UK FCDO, OECD speakers emphasised the importance of citizen engagement in innovation policy and the continuous strengthening of innovation ecosystems at national and sub-national levels, noting that it is essential to understand and address barriers to civil society engagement. Caroline Paunov and Luke Mackle shared lessons on balancing consultations and top-down policymaking within an ecosystem, building on their recent publications Engaging Citizens in Innovation Policy (2023); How to best use STI policy experimentation to support transitions? (2024); and Stakeholder engagement and collaboration in STI for the green transition (2024).

Figure 4: Paunov, C. and S. Planes-Satorra (2023), “Engaging citizens in innovation policy: Why, when and how?”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 149, OECD Publishing, Paris

A key takeaway from the seminar was that the role of the public sector is shifting from a facilitator of innovation and technology development to an active orchestrator. This transition presents an emerging set of challenges for decisionmakers and ecosystem stakeholders to navigate, particularly with regard to strategic direction, governance and policy design and implementation. A more involved, orchestrating role can be observed frequently in the development of frontier technologies linked to green transitions and economic resilience. Depending on the results of thorough diagnostics and the readiness of private sector players, governments increasingly link their innovation policies to broader strategic economic and development goals.

OECD STI experts presented an analysis framework that asks policymakers five key questions at each phase of the process:

Strategic choice and direction: How to decide which technologies to focus on?

Governance models: What kind of governance setup works best for the frontier technology initiatives?

Supporting collaborative innovation: How can the frontier technology initiatives help research and industry work together?

Overcoming challenges: How do ecosystem challenges vary according to technology?

Adapting under uncertainty: How can initiatives respond to change and unpredictability?

Leveraging existing data sources to diagnose local ecosystem maturity levels

Before this session, the OECD Innovation for Development Facility team consulted innovation leads from more than 20 DAC member countries and other funder organisations. Insights from this consultation and contributions throughout the seminar made clear that there is a challenge not only with available data, but with sensemaking expertise in funder organisations and implementing agencies. To address the former challenge, the OECD Innovation for Development Facility developed an pilot product for programme officers and policy experts, which consists of a repository of existing data sets and indices related to innovation ecosystems. This ‘minimum viable product’ – which will be further refined and developed with the learning journey’s participants – provides an overview of how and where to access existing data sets.

Throughout the seminar, many participants noted difficulties related to several other aspects of innovation ecosystem diagnostics. These included:

How best to navigate and map the social dynamics and networks within a given country, and practical approaches for capturing and incorporating these in diagnostic assessments.

Once a baseline is established, how to move beyond output-level measurements to capture changes in relationships, capabilities, and institutional dynamics at the ecosystem level.

Moving Forward

Looking ahead, this adaptive seven-part learning journey will respond and dedicate time to the above data and social networking challenges, and focus on monitoring and evaluation frameworks for innovation ecosystem strengthening in upcoming sessions. Participants will explore how to capture system-level changes, share concrete indicators, and reflect on methods for assessing stakeholder contribution. Colleagues are encouraged to bring examples, tools, challenges or questions from their work, which will help shape a shared approach that is grounded in practical realities and responsive to emerging challenges.

If you are practitioners working on strengthening innovation ecosystems in LMICs and want to get involved, please get in touch via indef@oecd.org