OECD Ecosystem Strengthening Learning Journey Series Session Three

Embedding Inclusiveness in Innovation Ecosystems

Authored by Benjamin Kumpf and Shad Hoshyar

This note summarises the discussion of the virtual seminar on October 30th, 2025, on innovation ecosystem strengthening, convened for development funders by the OECD Innovation for Development Facility in collaboration with the International Development Innovation Alliance (IDIA). This seminar is part of a nine-month learning journey that aims at advancing peer-learning among funders and generating new insights to inform better practices.

How Can Innovation Ecosystems Deliver Equitable Benefits and Opportunities?

This question guided the third session of the OECD Innovation Ecosystem Learning Journey, convened on October 30, 2025, in collaboration with the International Development Innovation Alliance (IDIA). The session brought together experts from members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee, from multilateral development banks, innovation funds and members of the Innovation Agencies in Africa Network to explore how inclusiveness can be embedded into innovation ecosystem strengthening efforts in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Participants agreed on one thing: exclusionary dynamics are inherent to any complex social system. As such, inclusiveness must not be an add-on. Policy makers and funders from international development organisations must approach inclusiveness considerations at every stage of ecosystem shaping efforts; from agenda-setting to participation and outcomes.

While virtually all policy makers and development organisations share ambitions to leave no one behind, operationalising inclusiveness ambitions remains complex. This session unpacked what inclusiveness can means in practice and how funders can assess trade-offs in practice.

Five Dimensions of Inclusiveness in Innovation Ecosystems

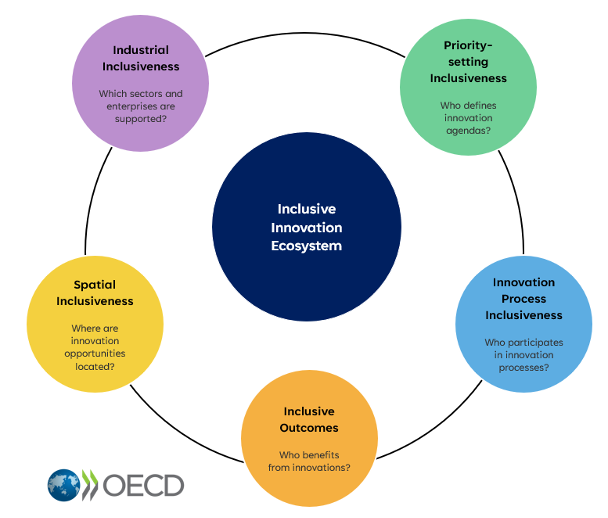

Figure 1: Inclusive Innovation Ecosystem framework, Benjamin Kumpf, OECD, 2025

Benjamin Kumpf, Head of OECD’s Innovation for Development Facility, introduced a framework, building on the 2017 OECD report ‘Inclusive innovation policies: Lessons from international case studies’. The framework identifies five pillars that can help policy makers and development funders assess and strengthen inclusiveness in innovation ecosystems and identify trade-offs:

Priority-setting Inclusiveness: Who defines innovation agendas?

Decision-making processes shape priorities and policies. Inclusiveness here means ensuring diverse actors—not just funders or “usual suspects”—have a voice in setting the direction. This is critical because agenda-setting determines which problems get solved and whose needs are prioritised.Innovation Process Inclusiveness: Who participates in innovation processes?

This pillar looks at who gets to engage and who receives support—such as finance, capacity-building, and access to platforms. Without deliberate inclusion, marginalised groups often remain excluded from opportunities to innovate and influence.Inclusive Outcomes: Who benefits from innovation?

Beyond participation, this dimension focuses on equitable distribution of benefits and incentives for innovators to address poverty and inequality. It asks whether innovations reinforce existing disparities or actively reduce them.Spatial Inclusiveness: Where are innovation opportunities located?

Efforts often cluster in urban centres, leaving rural and remote areas underserved. Inclusiveness requires targeting these regions and bridging gaps between ecosystems to unlock hidden innovation potential.Industrial Inclusiveness: Which sectors and enterprises are supported?

Policies and programmes should prioritise sectors that advance equitable development, not just dominant players or high-tech industries. This matters because sectoral choices influence who benefits from innovation and which economic opportunities are created.

Together, these pillars provide a practical lens for funders and practitioners to identify gaps and guide strategies for more equitable innovation ecosystems.

Lessons from Research and Practice: Elizabeth Hoffecker’s Insights

Elizabeth Hoffecker, Director of MIT’s Local Innovation Group, brought over fifteen years of applied research and field engagement across LMICs to the discussion. Her keynote emphasised that innovation ecosystems are complex adaptive, place-based systems - communities of actors, institutions, and relationships that collectively enable innovation. Hoffecker argued that ecosystems must be understood not only by their components but by the relationships and shared purpose that connect them.

Conceptual Foundations

Hoffecker distinguished between:

Innovation systems: Broad institutional and policy frameworks shaping innovation at national or global levels.

Local innovation ecosystems: Grounded, community-based systems that reflect local realities and priorities, enabling people to create, adopt, and spread new ways of doing things.

This distinction matters because imported models often fail to address local needs. Place-based ecosystems, by contrast, can unlock context-specific solutions and foster resilience.

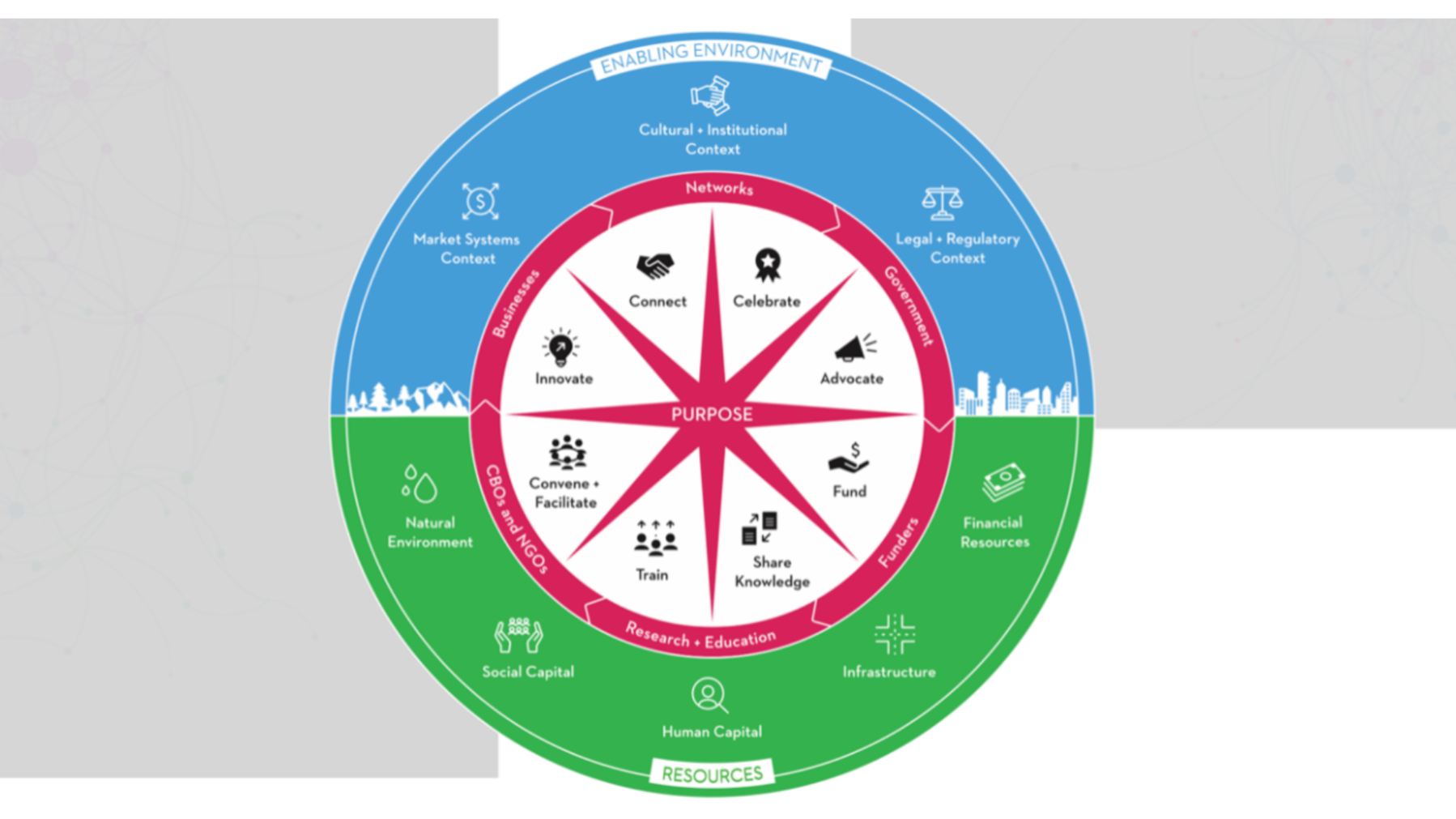

Figure 2: Hoffecker, Elizabeth. 2019. Understanding Innovation Ecosystems: A Framework for Joint Analysis and Action. Cambridge. MIT D-Lab

Framework for Inclusiveness

Building on Schillo and Robinson (2017), Hoffecker introduced a three-part lens for inclusiveness:

Agenda-setting (Leadership): Who defines priorities and governs the system?

Process (Participation): Who participates in innovation processes, and in what ways?

Outcomes (Results): Who ultimately benefits from innovation?

She stressed that most programmes focus on outcomes, but inclusiveness must start earlier - at agenda-setting and participation stages - to ensure systems genuinely reflect diverse voices.

This framework and the OECD model are complementary and can serve as practical tools to help identify and navigate priority-setting.

Common Pitfalls and Inclusive Practices

Hoffecker shared lessons from comparative research across Latin America and Africa:

Pitfall: Top-down agenda-setting driven by funders or elite actors.

Inclusive Practice: Use snowball referrals starting with local innovators and their networks.

Why: Local innovators best understand barriers and priorities.Pitfall: Reliance on elite conveners or ambitious plans that alienate local actors.

Inclusive Practice: Build trust through small-win pilots and visible results.

Why: Early, tangible successes foster legitimacy and engagement.Pitfall: Innovation outputs that reinforce inequalities.

Inclusive Practice: Embed inclusion goals into incentives and scaling mechanisms.

Why: Ensures benefits are equitably distributed.

Case Study: Guatemala

A participatory mapping exercise at Universidad del Valle de Guatemala revealed how spatial inclusiveness changes the picture. When only central campus actors were mapped, the ecosystem appeared dense but narrow. Including rural campuses uncovered new subsystems with distinct priorities - such as infrastructure and resource access - highlighting why inclusive agenda-setting must incorporate multiple perspectives.

Key Takeaways

Centre the local innovators, not the influencers.

Build inclusion iteratively through trust and small wins.

Align inclusiveness with system purpose—innovation should serve locally relevant goals.

Treat inclusiveness as system design, not outreach.

What Practitioners are Saying:

Breakout discussions explored three dimensions of inclusiveness — processes, outcomes, and spatial reach — surfacing practical lessons:

Inclusive Processes: Monitoring inclusiveness requires adaptive frameworks that go beyond counting participants. Funders are experimenting with relational indicators and tools like social network analysis to track voice, influence, and trust. Examples include Estonia’s D4D Hub, which uses peer-to-peer learning and joint reflection instead of one-way reporting, and New Zealand’s Pacific Innovation Hub, which embeds co-design and testing before funding.

Inclusive Outcomes: Benefits rarely flow automatically to marginalised groups. Intentional design, enabling environments, and adaptive procurement are essential for scaling inclusive innovations. Programmes like FCDO’s AT2030, which improves access to assistive technology for people with disabilities in 61 countries, show how global partnerships can deliver inclusive outcomes at scale.

Spatial Inclusiveness: Innovation often clusters in urban centres. Bridging gaps requires targeted policies, capacity-building, and collaboration platforms that connect innovators across geographies. Initiatives like Enable Morocco’s regional programmes and Estonia’s STEM education pilots in rural Kenya demonstrate how funders can operationalise spatial inclusiveness.

Across all discussions, participants emphasised that inclusiveness is a continuous learning process, not a fixed metric. Monitoring and evaluation must evolve from compliance to learning, capturing how power, voice, and relationships shift over time.

Moving Forward

Successful innovation can generate social benefits, and it can create new or exacerbate existing inequalities. As such, inclusiveness must be integrated throughout the ecosystem lifecycle: from agenda-setting to participation and outcomes. Funders play a pivotal role in shaping these dynamics through governance, funding criteria, and learning frameworks.

The next seminar in the OECD learning journey will take place on 25 November 2025, focusing on Alignment in Innovation Ecosystems. The session will explore how alignment can be strengthened by working with national partners, identifying demand, and putting locally led development principles into practice.

If you are working on strengthening innovation ecosystems in LMICs and want to get involved, reach out at indef@oecd.org.