OECD Ecosystem Strengthening Learning Journey Series Session Five

Directionality — Steering science, technology and innovation policies toward competitiveness and social and environmental outcomes

Authored by Benjamin Kumpf, Nicole Paul and Shad Hoshyar

This note summarises the discussion of the virtual seminar on 22 January 2026, on innovation ecosystem strengthening, convened for development funders by the OECD Innovation for Development Facility in collaboration with the International Development Innovation Alliance (IDIA). This seminar is part of a nine-month learning journey that aims at advancing peer-learning among funders and generating new insights to inform better practices.

This fifth session of the OECD IDIA Innovation Ecosystem Strengthening Learning Journey focused on directionality, and explored how science, technology, and innovation (STI) policies can be actively steered to address pressing social and environmental challenges while simultaneously strengthening national competitiveness.

During the session, Rym Jarou shared insights on Smart Africa’s work supporting digital entrepreneurship policies and Startup Acts across the African continent; Ilja Riekki discussed the Africa-Europe Digital Innovation Bridge project, which supports a range of African countries with strengthening innovation ecosystems, including joint work on evolving national policy planning, development and implementation support; and Piret Tonurist introduced findings from the OECD Mission Action Lab, focusing on how mission-oriented innovation can be adapted for the Global South.

What is directionality?

Directionality in innovation policy describes the “normative turn” in national and supranational science, technology and innovation (STI) policies over the last decades. The directionality of STI policies shifted from pursuing predominantly growth and competitiveness-related objectives to also addressing societal challenges. It brings together elements of innovation policy – focused on economic growth – and transition policy, which seeks beneficial change for society at large. The OECD suggests in the 2025 STI Outlook that “governments should consider a range of policy actions when reforming their STI policy mix to better contribute to transformative change agendas… policy support for national competitiveness can also contribute to resilience and security as well as sustainability transitions.”

Why does this matter for innovation ecosystem strengthening efforts?

A number of bilateral funders and members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC) as well as multilateral development banks, several UN and EU agencies and global innovation funds are implementing programmes and other initiatives specifically aimed at strengthening innovation ecosystems in low and middle-income countries. Many of these initiatives entail support for national partners regarding policy design and implementation.

This session sought to provide an overview of ongoing efforts related to national innovation strategies in selected countries, along with a deep dive in startup acts and in mission-oriented innovation, to share emerging good practices and support further coordination among international funders and with national innovation agencies.

Shaping policies that power Africa’s innovation ecosystems

Rym Jarou (Director, Smart Africa) presented the organisation’s work related to digital entrepreneurship policies and Startup Acts across the African continent. Innovation across Africa has sparked a substantial amount of attention among policy makers and international organisations, among others. There is considerable momentum as economies grow and more “African unicorns” emerge. Over the past years, a variety of policy initiatives were introduced by African countries such as Tunisia, Senegal, Ghana to help spark and scale innovative start-ups in their respective countries. Experiences from across the globe show that designing such policies is a challenging undertaking. It requires a good grasp of local innovation ecosystems and its dynamics, the scaling potential in a given context as well as mechanisms to engage not only core ecosystem players but wider parts of society. Rym highlighted that while there is strong continental momentum around Startup related policy framewors, national approaches vary significantly depending on ecosystem maturity, political economy, and strategic objectives. She shared these observations across country contexts:

Bottom‑up policy demand: In many countries, Startup Acts emerged from ecosystem actors and entrepreneurs pulling governments into action, rather than top‑down initiative.

Entrepreneur‑centred focus: Most Startup Acts remain sector‑agnostic and focus primarily on entrepreneurs, rather than taking a whole‑of‑ecosystem approach. As a result, many policies insufficiently recognize and provide support for startup-like initiatives stemming from small or medium-sized enterprises.

Implementation gap: The adoption of Startup Acts has outpaced implementation in most contexts. Tunisia remains a rare example of a country that has moved into effective implementation, impact measurement, and policy revision.

Critical success factors: High‑level political sponsorship, strong public‑public and public‑private dialogue, clear institutional accountability for implementation, and alignment with broader policy frameworks.

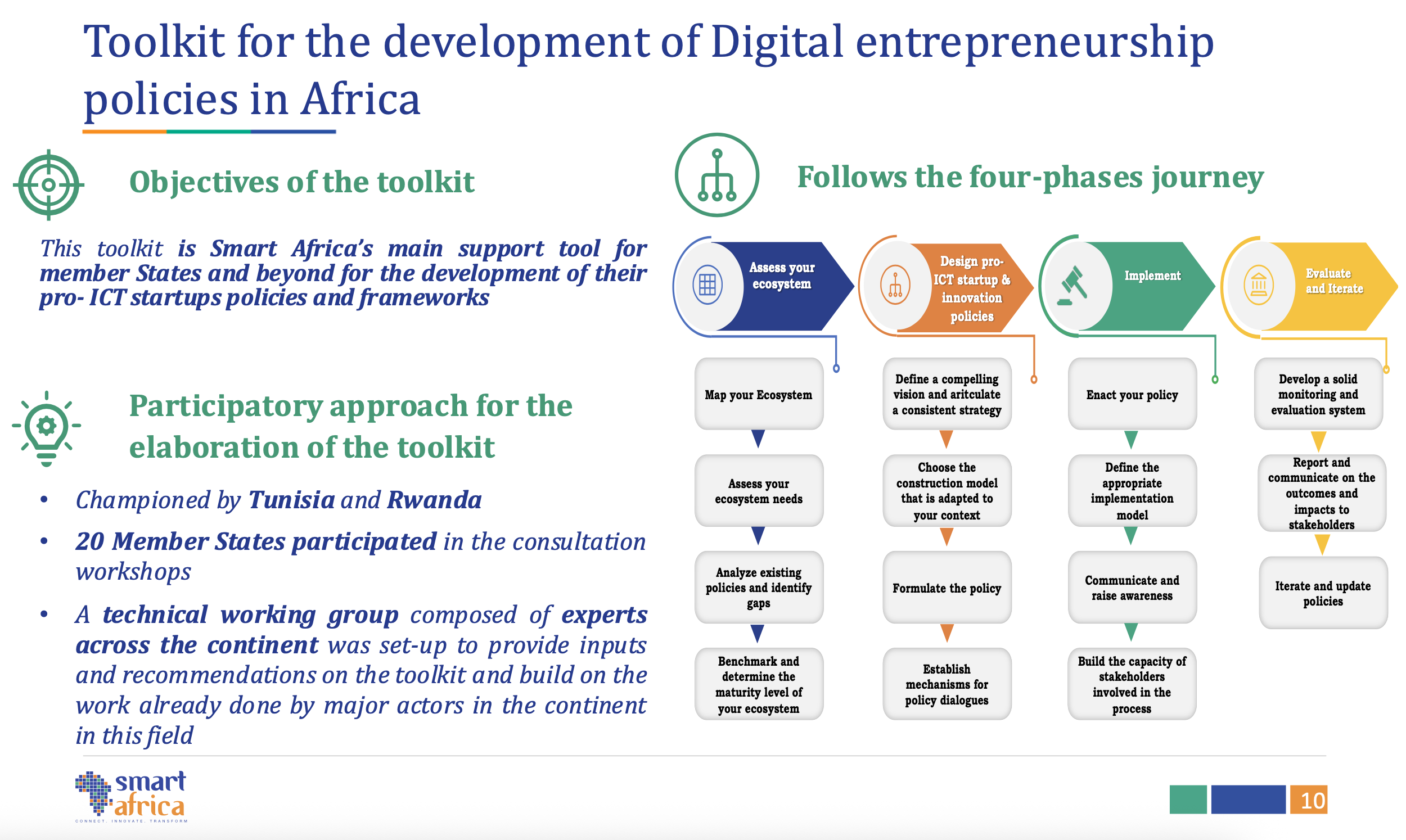

Rym illustrated these dynamics through the Tunisian Startup Act, emphasizing the importance of having implementation arrangements ready at the time of policy adoption and of embedding iterative review and learning mechanisms. She furthermore shared Smart Africa’s toolkit for policy-makers to support the design, launch and implementation of startup acts.

Figure 1. Smart Africa’s four-phase journey for designing and implementing digital entrepreneurship policies.

Team Europe Initiative D4D: Africa–Europe Digital Innovation Bridge

Ilja Riekki, innovation expert from the Finnish Institute of Public Management (HAUS), introduced the Africa–Europe Digital Innovation Bridge (AEDIB) under the EU’s Global Gateway and Digital for Development (D4D) Hub. The initiative aims to strengthen digital innovation ecosystems across 14 Sub‑Saharan African countries by addressing bottlenecks related to finance, skills, policy, and ecosystem coordination.

Ecosystem‑level intervention logic: AEDIB combines innovation policy support, ecosystem strengthening, and access to finance, rather than treating these as isolated components.

Policy in practice: Planned activities include ecosystem mapping, needs assessments, and the development of national innovation policy roadmaps, support on institutionalization, service design and delivery, further facilitated by peer learning and capacity‑building resources.

From adoption to delivery: Ilja emphasized the importance of clear mandates, prioritization, and breaking objectives or reforms into achievable milestones to support implementation.

Regarding the implementation challenges outlined by Rym in the first presentation, Ilja, emphasized that implementation often, unfortunately, stalls due to unclear mandates within government. Thus, identifying exactly "where" a each policy sits and who has the authority to drive change is critical for implementation success.

Figure 2. Core intervention areas of the Africa–Europe Digital Innovation Bridge (AEDIB) programme.

Mission oriented innovation: implications for the Global South

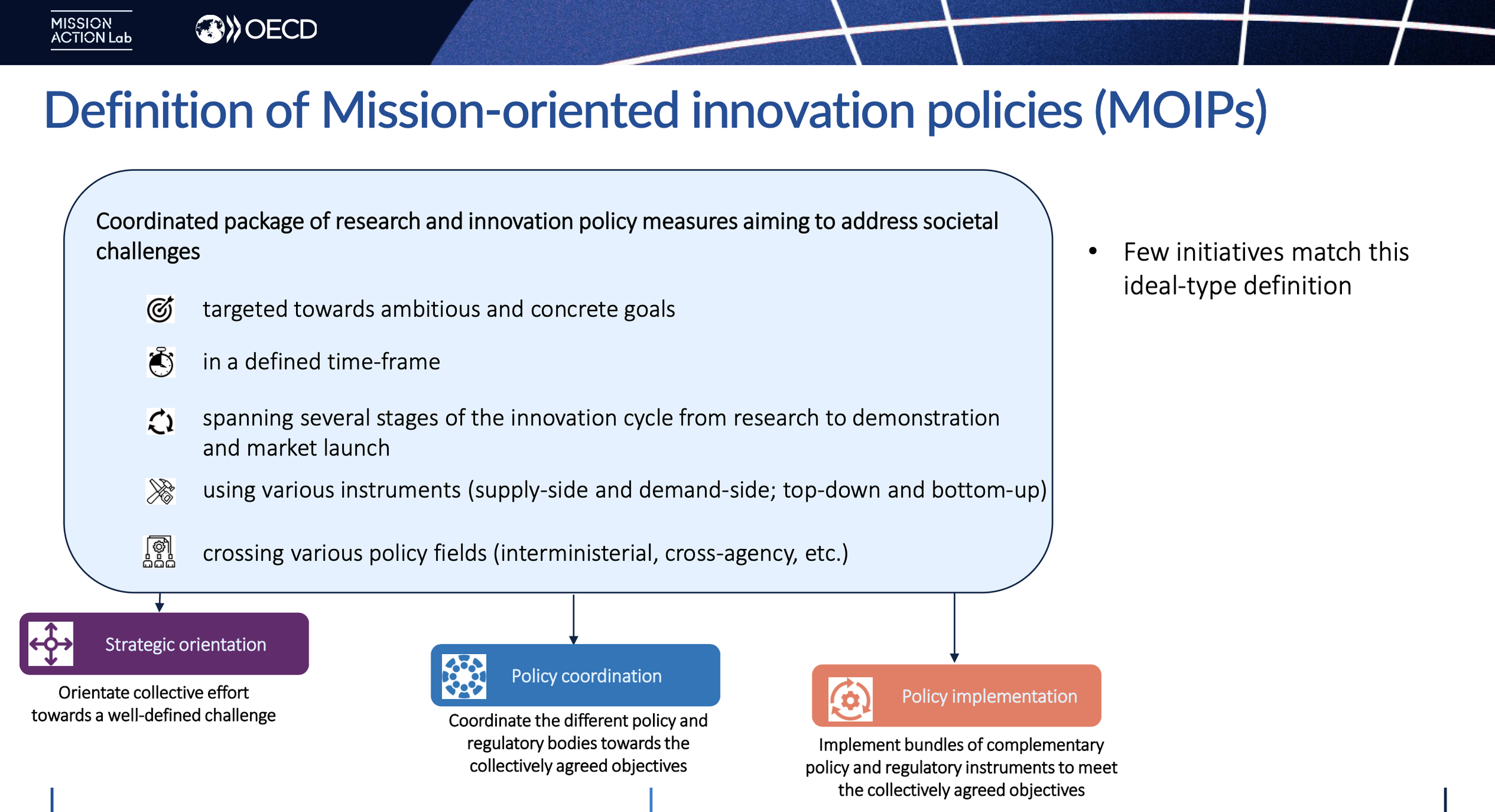

Piret Tõnurist introduced findings from the OECD Mission Action Lab, focusing on how mission-oriented innovation can be adapted for the Global South. Firstly, what is mission-oriented innovation? They entail a diverse mix of interventions and require government to take a lead role to collectively design and steer a portfolio of solutions. A mission approach seeks to deliberately shape markets, and to design and steer a portfolio of solutions that spans across traditional sectoral and technology boundaries (see: A brief guide to mission terminology, and OECD Mission-Oriented Innovation Policies Online Toolkit). In summary, mission-oriented innovation policies are coordinated packages of STI policies designed to address clearly defined, time‑bound, and ambitious societal or economic challenges.

Figure 3. Definition and core characteristics of mission-oriented innovation policies (MOIPs).

Piret emphasized that the interest in mission-oriented innovation continues to grow among policymakers worldwide. Over the past five years the OECD Mission Action Lab has observed a growing number of exploratory studies and new programmes in low and middle-income countries related to mission-oriented innovation and an increasing interest in the approach among members of the OECD Development Assistance Committee. Compared to OECD member countries, the approach remains emergent in the Global South. To inform potential future practice, led by governments across low and middle-income countries and led by international development organisations, the OECD Mission Action Lab is synthesizing evidence from across the globe to support policy makers with contextualizing mission approaches to the specific contexts. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) typically operate under institutional and resource constraints that differ markedly from high-income settings: even more fragmented governance systems, reliance on external development finance, and relatively weaker institutional capacities. These structural constraints influence both the feasibility and the design of mission approaches, for example, the challenge of aligning Official Development Assistance with domestic innovation systems in contexts of high external dependence.

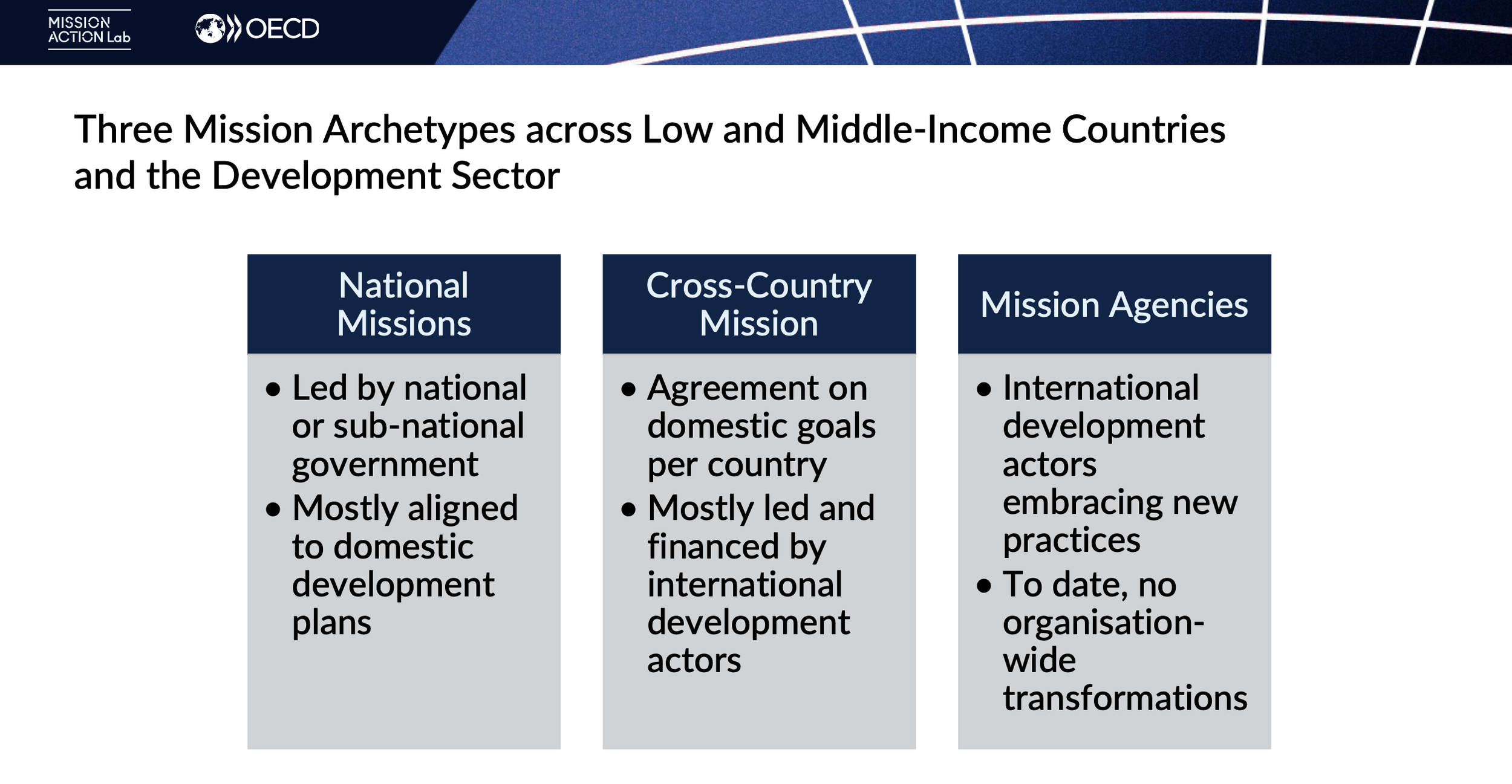

In the international development cooperation sector, there are currently three archetypes of missions.

1. Missions launched and led by national or subnational governments, such as India’s Jal Jeevan mission.

2. Missions led by national governments with strong involvement from international partners in the design and implementation phases, such as the cross-country mission Family Planning 2030.

3. International development organisations that are exploring ways to embed a mission-oriented approach within their institutional strategies and programmes. This includes: supporting governments in the early phases of mission scoping, piloting mission-oriented initiatives, and/or making elements of a mission approach a condition for their support. An example is the German Cooperation for International Collaboration (GIZ) and its support in action-research in mission-oriented innovation in partner countries to assess future options to support missions.

Figure 4. Mission archetypes in low- and middle-income countries and development contexts.

To support emerging and future mission-oriented innovation efforts along all archetypes, the OECD Mission Action Lab is currently finalizing a tool specifically for policy makers in the Global South, the Mission Readiness Assessment.

This tool focuses on the mission readiness of relevant context variables, namely

· public sector capacities and capabilities

· innovation ecosystem maturity; and

· dynamics of the international development cooperation sector.

The overarching objective is to support policy makers with practical diagnosis and prognosis: an assessment of existing and needed capacities and context factors. This is in turn can help to design, launch and implement missions that are deliberately addressing gaps and capacity constraints.

During the discussion, Piret shared further insights on governance arrangements related to cross-sectoral missions and their potential durability beyond election cycles. She outlined the need for:

Dedicated task forces or teams with full time capacity;

Strong mandates and high level political backing;

Governance structures that include non-government stakeholders to enhance durability beyond political cycles.

Moving from policy adoption to implementation: What are the key enablers?

Participants and speakers discussed the challenges and opportunities to move from policy to policy adoption, to implementation. Clear institutional mandates and political anchoring, as well as early involvement of implementing ministries and agencies, prioritisation and sequencing of reforms, and measurement, learning, and iterative policy adjustment were highlighted as key actions to ensure effective policy adoption and implementation.

Additionally, effective directionality depends on meaningful engagement with ecosystem actors. Participants highlighted the importance of:

Participatory policy design processes;

Mechanisms that de‑risk entrepreneurship (e.g. paid leave schemes, IP support, investment guarantees);

Partnerships grounded in local needs assessments rather than imported models.

Key takeaways

Directionality is not new, but its intentional use through policy design, ecosystem governance, and mission‑oriented approaches is becoming increasingly important to navigate unintended effects of successful innovation, such as inequalities between regions, exacerbation of inequalities due to digital divides and more.

Strong policy frameworks alone are insufficient; implementation capacity, institutional clarity, and learning systems are critical.

Ecosystem maturity and context matter: there is no single best practice for directing innovation systems. What is required in addition to the elements listed above is political will for key objectives of directional STI policies and mission-oriented innovation initiatives across political spectrums, and with a strong support by (parts of) the populus.

Mission‑oriented innovation offers promise for LMICs, but only where foundational governance and ecosystem conditions are in place. International funders and policy makers in LMICs should be cautious to invest in mission initiatives due ‘hype cycles’ before carefully assessing maturity levels of their government capabilities and capacities, innovation ecosystem maturity and the dynamics of the international development cooperation sector.